| EXHIBITION::: Everything is Made of Light (W/ Mary O'Neill, Isabella Streffen and Matthew Pell)) |

| PUBLIC LECTURE::: Interfaces of Nearness: Documentary Photography and the Representation of Technology |

|

EXHIBITION::: A Human Laboratory

|

| EXHIBITION::: DHP (Double Happiness Projects) |

| Artist Talk::: Western University |

| RECENT EXHIBITION::: ArtLAB Gallery - London

|

| AudioLodge Performance::: In Conjuntion with INTSTRUMENTAL

|

| RECENT EXHIBITION::: Exhibition at Art Gallery of Mississauga Opening: Thursday, May 5, 2016 Artist Talk: Sunday, June 12, 2012   |

| TEXT by Kendra Ainsworth

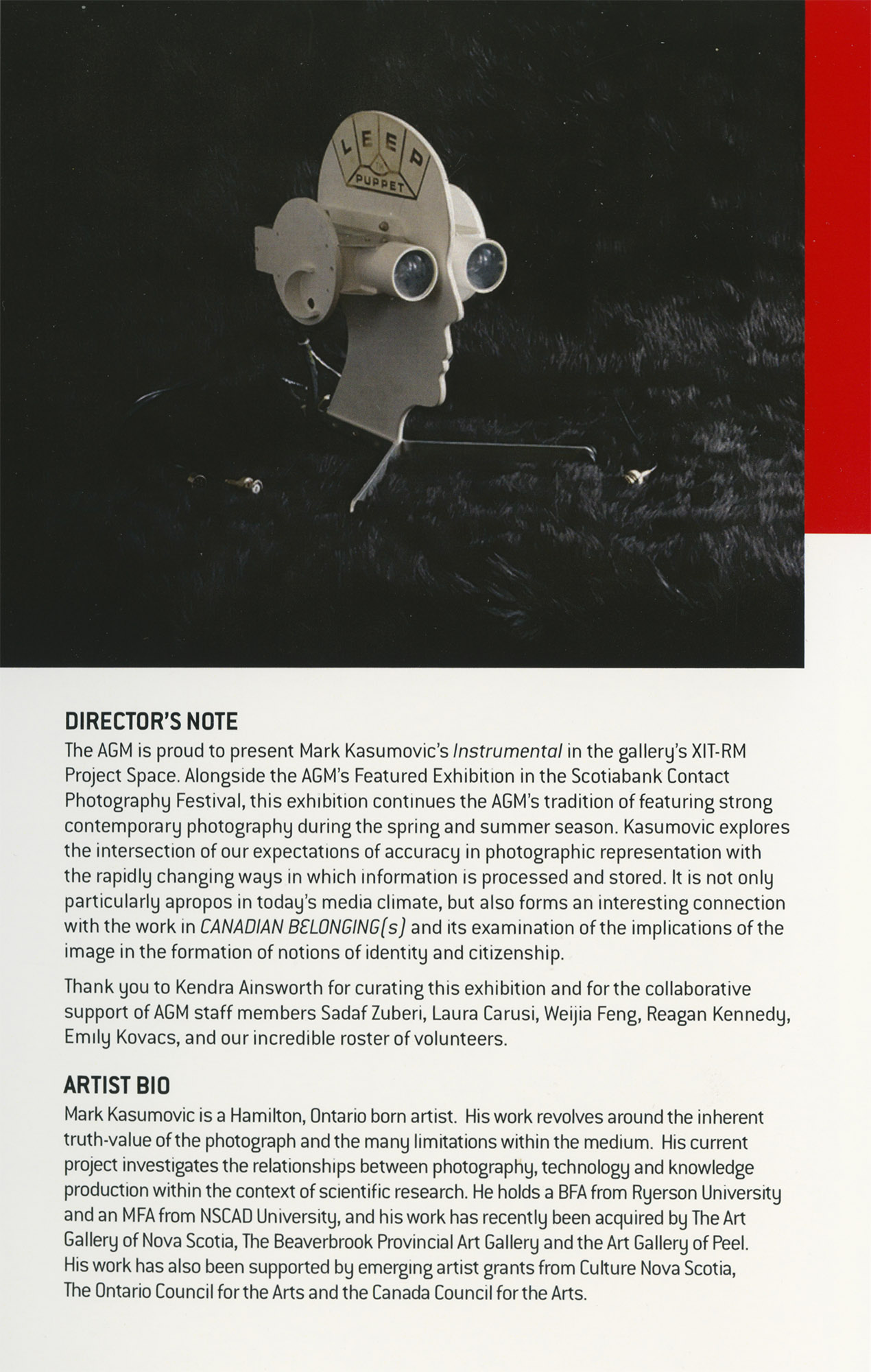

Mark Kasumovic’s photographic practice is informed by some of the principal concerns that have plagued photographers for years: the inherent truth-value of the photograph, and the limitations of the medium, particularly in our increasingly digital, networked world. As Walter Benjamin raised concerns over the loss of the “aura” of the art object as replication and reproduction of original objects became commonplace, so too does Kasumovic raise concerns over our understanding of information – visual, material, and intellectual – in a time when truth in representation seems increasingly called into question. Photography, although it captures that which is inherently fleeting (light waves/ particles, or in a more philosophical sense – time), has from its inception, been inextricably tied to the material world. Early photographs were captured on metal and glass plates, treated with chemical solutions, and produced as physical prints on photo sensitive paper. Today, however, a digital image is, as Kasumovic states, “a much more abstract construction …. a mathematical conglomeration of 1s and 0s that nothing less than a computer could intelligibly interpret. It is a coded message that simultaneously seems more complex and more akin to the reality it attempts to represent.”1 Kasumovic draws interesting parallels between the changing relationships of both photography and scientific information to the material world. As with the aforementioned shifts in photography, so too has science changed. Where once information about the world was collected mostly on slides and in test tubes, now it is collected and stored in data centres filled with huge server banks. Scientific instruments and research facilities that attempt to discover, see and map the invisible and unknowable (such as the CERN facility in Geneva, Switzerland, which uses particle accelerators to study the most basic constituents of matter) are emblematic of the larger shift in our culture in which information and images have taken on a primacy and importance that belies their ephemeral nature as merely pixels on a screen, light through fibreoptic cable. Kasumovic has travelled the globe, gaining entry to spaces not usually accessible to the public, to photograph the apparatuses that capture information that is equally elusive, but which is all around us, unseen. Artist and scholar Trevor Paglen, who has become known for his photographs of spy satellites, points out that while he exerts considerable effort tracking and documenting the paths of these objects, paradoxically, it is easier to see these satellites than it is to see what they see - information that is subsequently classified and locked away.2 Both Kasumovic and Paglen are, in a sense, exerting control over these ‘imageless’ domains of information by photographing the devices that collect it. By presenting these images in an immersive display that includes large scale vinyl prints and vitrines to create trompe l’oeil effects, Kasumovic draws attention to the ‘visibility’ of these spaces/ information, and encourages a more prolonged act of looking. By contrast to how we engage with images today, Kasumovic implies that not only must we pay closer attention to how we read images as representations of a concrete reality, but that we must question the existence of a concrete reality that can be transparently captured by photography. |

DOWNLOAD Full Catalogue::: Catalogue PDF  |